My

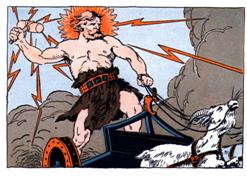

favorite story about knowledge and power concerns an ancient Macedonian called

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) He was called ‘the great’

My

favorite story about knowledge and power concerns an ancient Macedonian called

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) He was called ‘the great’ because he conquered the Persian Empire.

because he conquered the Persian Empire.THE AMERICAN ENGLISH EXPRESS Chapter 4 page 2

Is knowledge “facts”? Is it “truth”? Is it “wisdom”? Is it “power”?

My

favorite story about knowledge and power concerns an ancient Macedonian called

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) He was called ‘the great’

My

favorite story about knowledge and power concerns an ancient Macedonian called

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) He was called ‘the great’ because he conquered the Persian Empire.

because he conquered the Persian Empire.

Alexander was tutored by our friend Aristotle (see introduction) who was a cataloguer (collector, recorder) of knowledge, and was a collector of information. Aristotle’s teacher had been another Greek philosopher, named Plato (approximately 427-347 BC). You may have heard of him. Plato’s teacher was also a philosopher named Socrates (469-399 BC), who some consider to be the father of knowledge, because of his sacrifice for the right to ask questions to determine the truth.

Socrates

You see, Socrates was a teacher in ancient

Greece. He taught the youth of the city of Athens. He taught them that the act

of asking questions only  strengthened

one’s beliefs. If one believes that something is true, Socrates taught, then the

act of questioning and answering such questions would make much stronger one’s

conviction that what one believes is the truth.

strengthened

one’s beliefs. If one believes that something is true, Socrates taught, then the

act of questioning and answering such questions would make much stronger one’s

conviction that what one believes is the truth.

Socrates taught that it was good (beneficial) to ask questions about everything, so that one’s knowledge of everything could grow stronger. For example, asking yourself why you love your spouse can result in either a greater appreciation of our spouses (which would make the mutual love stronger) or a recognition that something is lacking (which if communicated to your spouse, and acknowledged, also could make the relationship stronger).

However, Socrates’ teaching method caused a problem, because the youth (teenagers) began to question the existence of the gods (the Greeks were polytheistic, they believed in more than one god; monotheistic is the term that designates belief in one god only).

The

leaders of Athens became upset and Socrates was arrested for ‘corrupting the

morals of the youth’ of the city. There was a trial and Socrates was found

guilty. The Athenians (who were the citizens because Athens was the first direct

democracy – all the free Greek males voted) gave Socrates a choice: he could

leave Athens forever (called “exile”) or he could drink poison and die.

The

leaders of Athens became upset and Socrates was arrested for ‘corrupting the

morals of the youth’ of the city. There was a trial and Socrates was found

guilty. The Athenians (who were the citizens because Athens was the first direct

democracy – all the free Greek males voted) gave Socrates a choice: he could

leave Athens forever (called “exile”) or he could drink poison and die.

Socrates chose to drink the poison, Hemlock,

rather than subvert (undermine) the search for truth. That is, instead of leaving his home in Athens, he stayed and sacrificed his

life for his beliefs: the best way to search for the truth is to ask questions.

Socrates’ way of teaching has become known as “the Socratic method”.

That is, instead of leaving his home in Athens, he stayed and sacrificed his

life for his beliefs: the best way to search for the truth is to ask questions.

Socrates’ way of teaching has become known as “the Socratic method”.

Plato used this method and so did Aristotle. Consequently, in my mind, there is a direct line between knowledge and power: Socrates taught Plato, who taught Aristotle who tutored Alexander, who conquered the world!

Now,

it is probably not due only to Aristotle’s tutoring skills (based on what he

learned from Plato, who learned from Socrates) that Alexander became ‘the

Great’. He undoubtedly had other people in his life from whom he learned and a

great deal of his own natural abilities. Nevertheless, as the thoughts of all

three of these philosophers were passed on to him in a direct line, one could

reasonably say that if knowledge is not power, certainly in this case,

knowledge became power. So, you decide for yourself whether

“knowledge is power.” Certainly, knowledge can make you powerful (full of

power).

Now,

it is probably not due only to Aristotle’s tutoring skills (based on what he

learned from Plato, who learned from Socrates) that Alexander became ‘the

Great’. He undoubtedly had other people in his life from whom he learned and a

great deal of his own natural abilities. Nevertheless, as the thoughts of all

three of these philosophers were passed on to him in a direct line, one could

reasonably say that if knowledge is not power, certainly in this case,

knowledge became power. So, you decide for yourself whether

“knowledge is power.” Certainly, knowledge can make you powerful (full of

power).

Is knowledge “facts”? Is it “truth”? Is it “wisdom”?

Let

us agree that there is one big thing: which we call ‘reality’. (By the way, this

is sometimes called ‘doing philosophy’.) We all believe that there is one

knowable, ‘objective’ (outside of and independent of ourselves) universe that we

perceive subjectively (from within ourselves, through our senses).

Let

us agree that there is one big thing: which we call ‘reality’. (By the way, this

is sometimes called ‘doing philosophy’.) We all believe that there is one

knowable, ‘objective’ (outside of and independent of ourselves) universe that we

perceive subjectively (from within ourselves, through our senses).

In

other words, there is one real world, we all live in it; it is the same for all

of us, even though each of us interacts with it in their own way. We each

develop our own perceptions and our own belief systems. Each of us views the

same world through our own unique ‘spectacles’, as Immanuel Kant would say.

In

other words, there is one real world, we all live in it; it is the same for all

of us, even though each of us interacts with it in their own way. We each

develop our own perceptions and our own belief systems. Each of us views the

same world through our own unique ‘spectacles’, as Immanuel Kant would say.

Copyright: 2004 English 4 All, Inc.